The Education of Alex Rodriguez

Six months, four cities, two coasts and one Batman suit -- we chronicle the fallen slugger's winding road back to pinstripes.

Editor's note: This story contains explicit language.

As part of the stories of the year collection, this piece is being resurfaced along with others in the coming days as ESPN Digital and Print Media closes out the year.

HE BURROWS DOWN into his hooded sweatshirt, slumps down into his padded chair, tries to blend into the background, and it works: For once in his life he actually manages to not draw attention to himself. But then the professor stands up and starts to say something truly -- insane. Something that threatens to ruin everything. On the first day of every new class, the professor says, I like to go around the room and have my students tell a little about themselves, so right now let's have each of you say your name, what you do for a living, and a bit about why you decided to enroll in Marketing 644 ...

The professor points to a young woman down front, and she doesn't hesitate, she instantly shifts into filibuster mode, telling the class that she works at UPS, and that she hopes to one day earn her MBA, and that she wants to become a blah blah. There are two dozen students in the classroom, and one by one they follow her lead, serving up their micro memoirs, then tossing it to the next student, and the next.

He watches them closely, listens carefully, envies them their neat, tidy life stories, and their intellectual confidence. His life is a mess, as everyone knows, and he often feels intellectually overmatched, because he didn't go to college. No father, no college -- these are his two gaping wounds, his two great sorrows. They're also a huge part of why he's here today, but no, no, he doesn't dare go into all that, doesn't want to tell these students anything about himself, let alone everything, including his darkest secrets, and yet here it comes, the invisible baton of attention, wending its way around the room, not unlike a baseball going around the horn. In fact, if the classroom were a diamond, he notices, by pure chance his seat would be the hot corner.

And then it happens. The student beside him is finished speaking and the classroom is churchly quiet and he's up. At least by now everyone is so bored that no one bothers to turn around. He addresses the backs of their shoulders and baseball caps. He tells them his name, Alex Rodriguez. He tells them his job, third baseman for the New York Yankees. He tells them he owns several businesses, so he's taking this class because he wants to learn about ...

Slowly, ever so slowly, the two dozen students turn and stare, their mouths hanging open. They know who he is, of course. Half the planet knows. He's in the news every day. He's that baseball dude who got banned for steroids or something, which makes him more than famous. He's, like, infamous, and dangerous, and kind of cool, a cross between Babe Ruth and Count Dracula. He keeps talking, and the students keep staring, and none of them can process what's happening, or what he's saying, because though he's sincerely trying to explain, to give a brief accounting of himself, he's totally failing to answer the only question running through their minds.

What the hell is A-Rod doing in my marketing class?

He's not sure himself. Like everything else in his life, it's complicated.

But it's also not that complicated. It's painfully simple. He's here because he needs an education. He's needed one for a long, long time.

And this year, whether he likes it or not, he's going to get it.

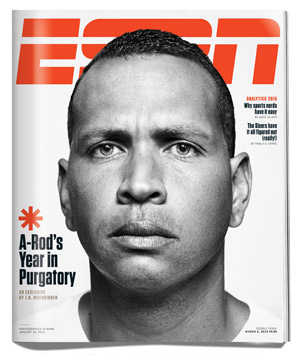

text

Peter Hapak

PEOPLE HATE HIM. Boy, wow, do they hate him. At first they loved him, and then they were confused by him, and then they were irritated by him, and now they straight-up loathe.

More often than not, the mention of Alex Rodriguez in polite company triggers one of a spectrum of deeply conditioned responses. Pained ugh. Guttural groan. Exaggerated eye roll. Hundreds of baseball players have been caught using steroids, including some of the game's best-known and most beloved names, but somehow Alex Rodriguez has become the steroid era's Lord Voldemort. Ryan Braun? Won an MVP, got busted for steroids, twice, called the tester an anti-Semite, lied his testes off, made chumps of his best friends, including Aaron Rodgers, and still doesn't inspire a scintilla of the ill will that follows Rodriguez around like a nuclear cloud.

Schadenfreude is part of the reason. Rodriguez was born with an embarrassment of physical riches -- power, vision, energy, size, speed -- and seemed designed specifically for immortality, as if assembled in some celestial workshop by baseball angels and the artists at Marvel Comics. He then had the annoyingly immense good fortune to come of age at the exact moment baseball contracts were primed to explode. Months after he was old enough to rent a car he signed a contract worth $252 million. Seven years later: another deal worth $275 million. Add to that windfall another $500 million worth of handsome, and people were just waiting. Fans will root for a megarich athlete who's also ridiculously handsome (body by Rodin, skin like melted butterscotch, eyes of weaponized hazelness), but the minute he stumbles, just ask Tom Brady, they'll stand in line to kick him in his spongy balls.

“No father, no college: Those are his two gaping wounds.”

-

Rodriguez's defenders (and employees) are quick to say: Sheesh, the guy didn't murder anybody. But he did. A-Rod murdered Alex Rodriguez. A-Rod brutally kidnapped and replaced the virginal, bilingual, biracial boy wonder, the chubby-cheeked phenom with nothing but upside. A-Rod killed the radio star, and his fall from grace disrupted the whole symbology and mythopoesis of what it means to be a superhero athlete in modern America.

Some Rodriguez haters are less offended by his mortal sins than his venial ones. For them, it's all about the man's unerring instinct for the eye-scalding optic. Slapping the ball. Poking the Sox. Kissing the mirror. Dissing Jeter. Dating Madonna -- of all his liaisons, the most dangereuse. (From a PR standpoint, he'd have been better served dating Bernie Madoff. In fact, he'd have been better served riding a tandem bike down Broadway with Madoff on the back seat, ringing the little tinkly bell.) Other haters focus on the verbal more than the visual. They footnote their hate to some cringey utterance, of which there have been a few. Rodriguez is that inevitable byproduct of a more image-centric, less literate age -- a bilingual man who's not quite at home in either language.

And yet, if words have not been his friend, they've often been his accomplice. No matter where you come out on Rodriguez -- insufferable phony, tainted legend, harried scapegoat, fallen angel, flawed human -- it's hard to make the case that he's a jolly good fellow, because there's one fact nobody can deny. On multiple occasions Rodriguez has looked directly into TV cameras and radio microphones, into the faces of fans and friends and reporters, and said things that were flatly untrue.

How many pills, creams or needles he used, how much those pills, creams or needles might have enhanced his already towering gifts, and to what lengths he went to conceal it -- these and other questions will be debated forever, and will never fully be resolved, but there's no longer any debate about Rodriguez's credibility. He's a proven liar, a repeated liar, and thus, as he prepares to emerge from the longest steroid-related suspension in the history of baseball, as he readies himself physically and mentally for his 21st spring training, there's tremendous interest in his story, but there's just no point in quoting him.

More than no point, there's just no way.

Take a sentence from Rodriguez, set it between two quotation marks and watch what happens; it curdles like year-old milk. The words become unstable, unusable, weirdly ironic. It's not a choice, to quote or not to quote, it's simple science, obeisance to strict natural laws, to the crazy alchemy between his damaged credibility and basic punctuation. Quoting Rodriguez is like dropping a Mento into a Diet Coke. It makes a big whoosh, everyone gets excited, for about three seconds, and then it's just a mess, and you wonder what's been accomplished, besides some stickiness, and maybe a permanent stain.

In fact, don't even bother taking out a recorder or notebook in Rodriguez's presence. Aside from the fact that it induces in him a physical condition, Resting Zombie Face, and aside from the fact that he says off the record more than an allergist says gesundheit, he's forfeited his right to exactitude. No more verbatim for him. Not right now. His suspension is over, but so is the public's suspension of disbelief. If he hopes to recapture the public trust, to repair his image, it will be through actions, not words. All human happiness or misery takes the form of action, Aristotle said, and though he was speaking of storytelling, life is a never-ending story, and what holds for plot often holds for ethics. Rodriguez, deep down, knows this. He knows he's not talking his way back from purgation. Reminded, he nods, I know, I know, you're right. And then he's condemned to learn it again, and again.

For instance: He drives one night from his office in Coral Gables, Florida, to a college in downtown Miami to attend a lecture by Magic Johnson and billionaire Mike Fernandez. The two are speaking about their many successes in business, and hundreds of aspiring entrepreneurs are on hand. At one point Magic asks the crowd to recognize a few luminaries in attendance. We got Ray Allen! Thunderous applause. And over here we got Alex Rodriguez! More applause, only slightly less thunderous.

Later, at a café in the Design District, sharing a plate of grilled fish and some calamari with a friend, Rodriguez glows. Uplifted, emboldened by that applause, he talks about how badly he wants to get back and play, help the team, blend into the team, have it not be about him anymore, and his words are unusually cogent, his tone nakedly earnest, altruistic. He's once again that phenom with nothing but upside. He looks hopeful, sounds hopeful, and while there's something stirring about such hope in the face of so much hate, it also seems uncharitable to continue hating in the face of such hope. When asked how it all sounds to her ears, however, his friend frowns. Total bullshit, she says.

Rodriguez's face falls.

I believe you, the friend says. I know you mean it. But your words aren't going to convince anybody.

Rodriguez looks down. He studies the grain of the wood table. He looks as if the calamari suddenly isn't sitting right in his stomach. But he nods, he gets it.

Only a few players have more home runs than Alex Rodriguez. Debby Wong/USA TODAY Sports

NO ONE CAN say precisely when the education of Alex Rodriguez began. Certainly not Rodriguez; his mind doesn't work that way. And surely not the people around him. Like the Red Cross right after a South Florida hurricane, they've been a little busy. But they swear it's a thing, this education, this radical home schooling he's undertaken. And maybe it's an unfair question anyway. How do you measure the start of an evolution, a metamorphosis, an accretion of character? A learning curve isn't a home run's trajectory. It doesn't always start at home plate.

Still, one date jumps out. Jan. 12, 2014. Ish. He's sitting in his Manhattan apartment, sulking like Achilles, fuming like Milton's Satan, exhorting his troops to battle Major League Baseball, and commissioner Bud Selig, desperate to get a reduction of his 162-game suspension for using banned, performance-enhancing substances. He's pledged to fight to the death, to sue everyone, but today the fight has begun to feel doomed, futile -- wrong. He is, after all, at fault.

He reaches out to Jim Sharp, a feared Washington litigator, a Navy man, a plain-spoken Oklahoman in his early 70s, and on the phone Sharp puts it to him real straight: You're ruining your life.

That jolts him. That sinks in. That's the thing that makes Rodriguez stop and take stock.

He paces his apartment, as much as any man can pace after two hip surgeries. Just two years ago his doctor sanded and shaved the ball joint of his left leg, to make it fit more smoothly into the hip socket. Three decades of swinging a bat, of violently torquing his hulking 6-foot-3 frame, had caused a calcium buildup, and the buildup had become an impingement, and the impingement had begun to stop the rotation of the hip, not simply slowing Rodriguez's swing, causing him to look like a pigeon-specked statue at the plate in the 2012 postseason, but shutting down his lower torso. On the day of the surgery he couldn't lift his leg one half inch off an exam table.

Now, he sits. Through the pain, through the fatigue, he sees with new, dazzling clarity that Sharp is right. It's over. He calls off his dogs, tells his inner circle to issue a statement that he's dropping all litigation, accepting his suspension, effective immediately.

His inner circle tells him he's making a terrible mistake. Fight, fight, fight, they say -- one of them actually uses those words. So he redraws his inner circle. He forms a new inner circle, a smaller circle, this one made up of levelheaded Midwesterners, peacemakers -- and deal makers.

Worn out, depressed, verging on despair and unemployed for the first time in his adulthood, he locks himself away and takes a vow of media silence, which isn't easy. As Henry Adams says in The Education of Henry Adams: "He never labored so hard to learn a language as he did to hold his tongue ..."

Then he makes a list. He loves lists, makes them all the time, usually in one of his special yellow notebooks, and on this list he writes the names of people he must phone right away. People to whom he owes an apology. People to whom he owes an explanation. Friends, owners, fellow players with whom he should shoot straight. He goes down the list, one by one, dialing his BlackBerry with an unsteady hand. He tells each person on his list that he's deeply sorry for all the drama he's caused, that he's determined to regain their trust and he hopes they'll give him that chance. Of course, he doesn't tell them the whole story, because he's never told the whole story to anyone. Not a single person, living or dead, knows the whole story, though two people know something close. Still, he tells the list people more than he's accustomed to telling, more than he's willing to tell, which makes each call a crucible. He's relieved when the list voices thank him for the call and wish him good luck in the trying days ahead. Mercy, grace, compassion -- it's more than he hoped for, more than he deserves. It means he's on the right path.

Now he makes another list. People to whom he owes a special apology, a more complete and detailed explanation, and one that will be a thousand times more difficult to deliver. On this list he writes only one name.

Natasha.

Rodriguez has two daughters -- Ella, 5, and Natasha, 9. They're the first thing you see when you walk into his office, two enormous color portraits on the wall behind his desk, even before you see the MVP trophies. Throughout this scandal Rodriguez and his ex-wife, Cynthia, have been on red alert, scrambling to shield the girls, clicking off TVs, hiding newspapers. But soon, they fear, Natasha is going to hear something. She's old enough, her friends are old enough -- some arrow of derision or ridicule is bound to pierce her parental bubble. She's also smart, and any day now she'll be able to piece together all the little things that don't add up, like why Daddy is suddenly around all the time, why Daddy's able to drive her and her sister to school. She'll start to ask questions, and Rodriguez intends to pre-empt her questions with a flurry of answers. This will be a vital part of his suspension, he decides. If he does nothing else in the coming year, he must do this. Love is truth, and the way out of this dark place in which he finds himself is telling Natasha the truth.

Just not now.

Not in January 2014.

He's just not there yet in his education.

HE MEETS A friend for coffee at a bookstore café in Coral Gables. His game, his career, his life, it's all hanging by a hair. He tells her he's scared. He's really scared. She's known him since he was a boy, and she's never seen him like this. Before parting, they walk over to the self-help section and she helps Rodriguez find a book. Breaking the Habit of Being Yourself. How to Lose Your Mind and Create a New One.

Books, he tells himself, lots of books -- this too will be a vital part of his suspension.

Breaking the habit of being Rodriguez -- does this mean quitting baseball altogether? Maybe so. Maybe there's no other way, he thinks, and thus in these first tender days of banishment he spends hours and hours considering retirement. He's had two hip surgeries, he's 38 -- what's the point? Why not just give the people what they seem to want and fade away. Let go.

He stares into space, imagining how it will feel never to don pinstripes again, never to

dig into the batter's box again. Never to win. But he can't imagine it. He has a vivid imagination, but that he can't picture.

Which comes as no surprise to the people who know him best. This is a man whose idea of a perfect evening is polishing his bats. He has them custom made -- coal black, 34 inches, 32 ounces, triple-dipped, his name lasered on the barrel -- and few things give him more pleasure than shining them up, wiping them down with a soft cloth, meticulously examining the scuffs to see exactly where and how he's striking the ball. This is a man who breaks down everything into baseball terms. A difficult problem is a slider on the black. A stressful situation is a bases-loaded jam. A stressful situation with

no time to solve it is a bases-loaded jam in the bottom of the ninth. The top person in any line of work is the Babe Ruth of Such and So. Rodriguez always wants to know: Who's the Babe Ruth of your field? Who's the Babe Ruth of Writing? Who's the Babe Ruth of Banking? Who's the Babe Ruth of Baby-sitting?

No, no, he can't walk away from baseball, not yet, his love for the game is too strong. And he still has plenty of game left, he believes. He knows that if he can rehab his hip, get his mind right, he could be great again. Maybe only for a season, or half a season, or a game, but still -- to be great again. He owes that to the fans, the game, his team.

Of course, there's also the $61 million in salary he gets if he returns. He could say

that money doesn't matter, and he often does say it, but who in their right mind would believe him?

THE MERE CONTEMPLATION of retirement flings open the door to memory, and he can't get it shut again. His mind drifts back, like an infielder under a high pop fly. He can see the beginning, the first stirrings, sitting beside his father in their tiny house in Westchester, Florida, watching the Mets and Braves. The TV is ancient, the reception is atrocious, but his father, a former catcher in the Dominican Republic's professional league, doesn't care, so the 9-year-old Rodriguez doesn't either.

As long as they can see something, anything, cleated shadows mincing across a staticky diamond, they're good.

The father calls his son Pipiolo, Spanish for Young, or Naive, and he teaches Rodriguez all about the game, and still it's never enough. Rodriguez assails his father with questions. He wants to learn, of course, but the questions aren't really about education. The boy is trying to capture the old man's heart, hold his attention, which isn't easy, because his old man is a drinker -- two six-packs, every night -- and a gambler. He plays the horses, and bolita, a kind of lottery, and he loses more than he wins.

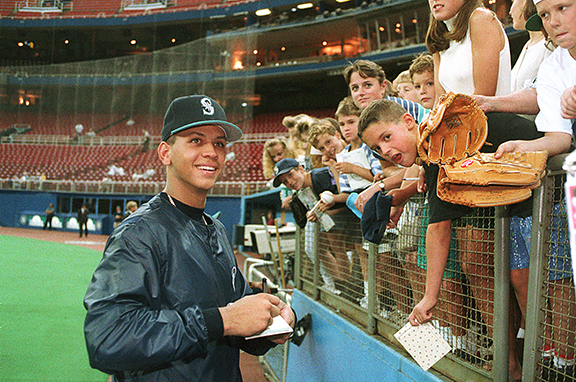

Rodriguez signs autographs after being drafted by the Mariners in 1993. Gary Stewart/AP Images

Then one day, when Rodriguez is 10, he comes home from school and the house is strangely still. The TV is off. His father is gone. His father's shoe store has been failing, so he's gone up to New York to scout locations for a new store. At least that's the story Rodriguez gets from his mother. He'll be gone only a little while, she says, and then a little while becomes para siempre.

Growing up, Rodriguez blames himself for his father's disappearance. Surely he did something, said something, to drive his father away. He hates himself, and also pities himself. He fears that not having a father will cripple him, hold him back in life. A father is an educator. A father teaches a boy about more things than baseball. A father teaches about money and women, about right and wrong. A father instills morals, discipline. Rodriguez's mother doesn't discipline. She's too sweet, and he's too big. Also, they both know that he's their only way out of this house, this neighborhood. So he can do no wrong. Early in his suspension it occurs to him with the force of revelation: My whole life, I've never been punished, never been told no -- until the 162.

But the worst part of losing his father? All those questions. He had so many more, and he never got to ask them. Thirty years have passed, he still asks. Everyone around Rodriguez says he asks questions constantly. Each conversation is an interrogation. It's his process, it's how he interacts with the world. It's how he learns.

It's also how he re-creates that lost paradise with his old man.

“Maybe only for a season, or half a season, or a game, but still -- to be great again. He owes that to the fans, the game, his team.”

-

TWO DAYS AFTER he surrenders, drops all litigation, Feb. 11, 2014, he gets an email from his friend Jose. Hey, need to talk to you. Urgent.

He worries. He dials Jose right away.

Are you sitting down? he asks.

Yes.

It's your father.

Rodriguez hasn't talked to his old man in years. Still, dios mio, it's his father. Gut punch, he calls it, and it lands when he's least expecting. Can it be mere coincidence, he wonders, that his father passes now, at the start of his suspension, in the dead of winter? He walks the streets, looks at the bare trees, hunches his shoulders against the February wind. Clearly the universe is angry with him, is penalizing him -- but for what? He doesn't dare go too far with that line of questioning.

Hours after receiving the bad news, he attends a talk by Malcolm Gladwell, who's just published a book, David and Goliath. Gladwell described Rodriguez in a 2013 essay as one of the most disliked athletes of his generation, but oh well. The book topic interests Rodriguez, and besides, readings and lectures and bookstores are his guilty pleasures. Especially bookstores. You can go in, he says, have a cup of coffee, and for an hour or two pretend you're smart.

This night, however, he's not feeling smart. He's feeling hopelessly distracted. While Gladwell is talking, Rodriguez is floating somewhere outside his body, time-traveling back, back, to the late 1990s. He can hear Cynthia urging him to find his father, to reconnect, before it's too late, and he can see himself finally heeding her advice, finding his old man, flying him up from Florida, to Minneapolis, of all places, where the Mariners are playing the Twins. Better to have the reunion in a small town, he and Cynthia figure, far from the paparazzi and prying eyes of larger cities.

He installs his father in a hotel near the one where the team is staying, and for four days he and Cynthia and his father pass the mornings and afternoons sharing meals, catching up. Rodriguez asks his father a million questions, but never the uppermost question. Why'd you leave? And his father never volunteers an answer.

Sometimes Rodriguez will slip and ask his father a question in Spanish, and his father always takes Cynthia's hand and admonishes his son: We have a beautiful woman in the room; we must speak in English.

At night they all head out to the ballpark, and Rodriguez is deeply touched to see his father wearing a dark suit and tie, befitting a special occasion. And it is special. Rodriguez has a reputation for shrinking in big games, but this series with the Twins is among the biggest of his career, his personal World Series, and he becomes a snarling, fearsome beast. Every ball he hits goes clanging off the wall, or sails over. The Twins wonder what they've done to piss off Alex Rodriguez; they don't know that this is the first time he's ever played in front of his father, that dapper gentleman in the front row who looks as if he just arrived on the 20th Century Limited from the 1940s, and Pipiolo is determined to make him proud.

Hitting a home run is a strange way of getting love, of giving love, but it works for Rodriguez, and always has. A home run doesn't just stop the game, it stops the world, lets you get off. A home run asserts control, announces wordlessly but unmistakably: You will ALL deal with me! Which feels so damn good after a childhood feeling powerless. You don't reach 654 home runs, fifth on the all-time list, without to some degree fetishizing power.

He thinks often of his early years in the league, playing for Seattle, desperately searching for his stroke. He sees himself driving home from the ballpark sobbing, punching the steering wheel, because earlier that night he got hold of a pitch and smashed it high into the seats, but the cavernous Kingdome, with its jet-propeller air conditioners, blew it back. To be robbed of a home run -- it's beyond endurance. He'd rather be robbed of his wallet and car keys. Every home run is precious, every home run has meaning. More, every home run has a separate identity, and a home run that fails to achieve its identity, to reach its full home run potential, is a tragedy.

He's hit 654 home runs, and each one, he says, is different. They're all like his children, he says. Each home run is his child.

TWO MONTHS INTO his suspension, April 2014, while the Yankees are hosting the Angels, Rodriguez is in Anaheim at the Milken Global Conference, a gathering of financial gurus, world leaders, all the Babe Ruths of money and power, plus scores of students eager to learn their secrets. Milken, who went to prison in 1990 for securities fraud, is one of the featured speakers, and it's strangely comforting for anyone in the crowd who's ever erred or fudged or sinned to see a felon presiding with such aplomb over this distinguished company. But that's not the pleasure of the conference for Rodriguez. For him it's all about being a student. Having his own desk. Taking notes in a notebook with pristine yellow pages. Feeling at the end of each day that he's learned something, that he's smarter than he was yesterday. This, he thinks -- this is what my suspension needs to be about.

Rodriguez runs into supporters while leaving MLB headquarters in 2013 after filing a suit against the league and commissioner. CARLO ALLEGRI/Reuters/Landov

When the conference wraps up, he reaches out to officials at the University of Miami, broaches with them the idea of taking a class at the School of Business. To what end? they ask. In other words, er, why?

Where to begin? Should he tell school officials that he's been obsessed with college since he was 17? Should he tell them that he wanted more than anything to follow all his high school friends to Gainesville or Tallahassee or Coral Gables, but he was the first pick in the 1993 draft and the money he stood to make was the salvation of his mother and his two half-siblings, Joe and Suzy? Should he tell them that his stealth hobby is visiting college campuses, that he's been to nearly 40 so far, that he almost always takes the campus tour, visits the bookstore and buys a sweatshirt and a backpack? Should he tell them that college represents normalcy, and serenity, that college is the place with all the answers? Should he tell them that he's already frantic about which colleges his daughters will attend, or that he recently suffered a meltdown when his nephew considered playing minor league ball instead of attending NC State? (Rodriguez spent hours with the nephew, pleading, bargaining, and finally got the kid shipped off to Raleigh.)

No. He just tells school officials that he might one day apply the class credit toward his undergrad degree, or his MBA, but that short-term his goal is simply to gain some classroom experience. To find out what kind of student he might be. To test himself.

When they say yes, when they offer him a spot in Marketing 644, he feels as if he's been accepted to Harvard. He takes his daughters to Target and they pick out three backpacks, one for Ella, one for Natasha, one for Daddy.

Just before the summer semester begins, however, school officials suggest that Rodriguez take a skills assessment. They need to know if he has the math and writing proficiency to keep up; otherwise he'll be wasting his time. And theirs. Dutifully, he sits at his computer, takes the assessment, and whoa, it's rougher than he feared. He takes it again. Still rough, but slightly better. At least he and the school now know what they're dealing with.

Then comes that intense first day, July 19, 2014, the professor going around the room, making everyone give their life stories. Is this a marketing class or an AA meeting? After the students recover from the shock of Rodriguez's presence, he manages to blend again into the background. Just another guy trying to get an education. Even when the class breaks into smaller groups, to focus on case studies, his group elects a leader and they don't even consider him. He's delighted.

Toward the end of the first class there's an exam. It covers the day's material and the preassigned reading. It's been two decades since Rodriguez last took an exam, so he's aware when he walks out of class that he hasn't exactly aced it. But he's not emotionally prepared for the professor's phone call a few days later.

You got a ... 44, the professor tells him.

In baseball 44 percent is a batting title. At the University of Miami it's an F.

Rodriguez is mortified. He can't remember when he's been so embarrassed. For three

days he doesn't sleep; he wanders around his house in Miami Beach feeling like a failure, a dummy. Eventually he forces himself to look over the test, to honestly critique his effort, and he realizes that he didn't work as hard as he could have. He didn't do all the reading. He vows to bear down before the next class, and in three weeks he manages to bring his grade up to a B.

He talks about that B the way he talks about 654.

He's not giving it back.

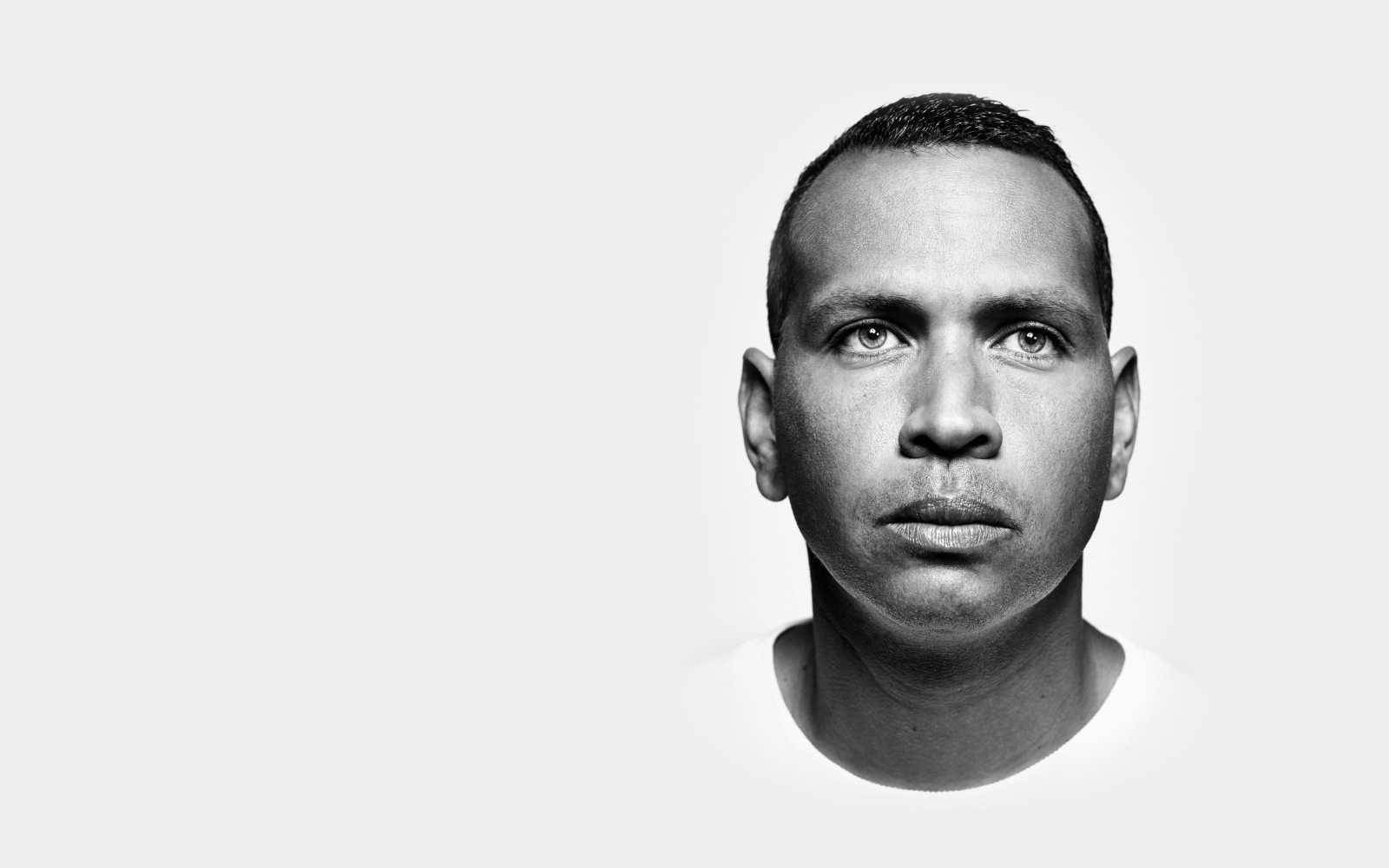

text

Ron Antonelli/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

BESIDES SCHOOL, AND his daughters, the centerpiece of his suspension gradually

becomes therapy.

He's been to psychiatrists before, and Cynthia is a psychologist, so he's familiar with the concepts, the language, he knows his way around transference and projection. Still, this kind of therapeutic approach is something else. More intense, more viscerally grueling.

Rodriguez sums it all up this way:

Dr. David goes deep, he goes hard, and he often draws blood. He almost seems angry with Rodriguez. Then again, who isn't these days? Like Zeus, the good doctor glowers down at the world from his mountaintop throne, and getting there, reaching Dr. David's remote and frosty corner of Olympus, is half the ordeal. Rodriguez hates flying there alone, hates driving alone up the icebound slopes, hates staying alone at the local hotel, which looks like a treehouse and doesn't have Internet or cell reception. He also hates eating dinner alone, and breakfast alone, and sitting alone on that cream-colored love seat in Dr. David's office, with Dr. David sitting across from him in his giant Sharper Image chair. Staring at him. For five minutes. Or 10. Waiting for Rodriguez to snap out of it, to wake up, to get it.

Over Dr. David's shoulder is a large picture window with a wide view of snow-topped peaks and a vast pine woods, a cold and alien landscape that reinforces Rodriguez's sense of dislocation. He hates it here, but hope overrides hate, and he keeps coming back. He never cancels. Dr. David is his last best chance for figuring out how he screwed up his life, and how to fix it, and how to speak to Natasha

when the time comes. The more he meets with Dr. David, the more he realizes that this upcoming meeting with Natasha -- maybe in December? January? -- is going to be everything.

He and Dr. David don't just talk about Natasha, however. They talk about love, trust, intimacy, marriage, abandonment, neglect, power. They talk about steroids. Dr. David is one of the two people who know something close to the whole story.

They talk about mind-mapping, which is how Dr. David describes the way human beings read each other, and about regressing, by which Dr. David means being blocked or immature or unevolved. They talk about perping, Dr. David's term for lying or conning or disrespecting or generally mistreating people. Actually, on second thought, it's not at all clear what perping is, not from Rodriguez's précis, but it sounds a lot like being an asshole, and after many months with Dr. David, Rodriguez concedes that he's done more than his fair share.

Soul-crushing, kneecapping, the sessions are spa days compared to what comes after. Dr. David banishes Rodriguez to the nearby woods, orders him to go on a walkabout of shame, to meditate on what they've discussed, ponder what he's done. For a man who doesn't like being alone, this solitary excursion into the wilderness with nothing but his regrets for company is the most exquisite anguish.

Rodriguez complains to Dr. David, and Dr. David doesn't care. Do it, he says, and Rodriguez obeys.

Back in Miami, Rodriguez also complies with Dr. David's mandatory nighttime journaling sessions. Each night, lying in bed, he fills one of his notebooks, pours out his heart, lets it all flow, baseball, fathers, mothers, abandonment, until his hand cramps. Then he sends the notebook off to Dr. David, who marks it up, uses it to shape their next session.

Some nights, after journaling, he'll lie awake, unable to sleep, strangled by self-accusations. It's so bad sometimes, he has to get out of bed, walk the floor. He thinks about his teammates, who at this moment are playing Kansas City, or Tampa Bay, or Chicago, and wishes he were with them. He berates himself. You had pocket aces! Pocket. Aces. And somehow you blew the hand. You could've walked away years ago. You could've grown a beard, gotten fat, and you'd have had a career to be proud of, and you'd be a lock for the Hall. But no. You had to -- had to --

To what? He doesn't say. He doesn't go into specifics, details, not to himself, not to others. Often, when The Subject comes up, people lean in, and wait, and he invariably leaves them waiting. It's not that he doesn't want to talk about it, he tells them. Legal issues, contractual stuff, lawyers, you know. He'd like to be candid; he just can't. But the reality is, he's still not there yet in his education.

The mere contemplation of retirement brings back a flood of memories to 38-year-old Rodriguez. Kathy Willens/AP Images

In January 2014 he met secretly with federal agents and admitted using banned substances from late 2010 until October 2012. So there isn't any mystery about what he did, or when. The mystery is how, and how much, and why, and he's unwilling to unravel that mystery. Or unable. There are two kinds of evasion: hiding the truth, and hiding from it. Rodriguez has done both, lots, but his evasions lately seem to fall into the second category. He appears to suffer from some interior blockage, like a repressed memory, one he doesn't know how to let out. Too shameful, too painful, too deeply lodged. Too integral. It's the glue that's holding him together. In the abstract, sure, he can apologize. He's happy to apologize. I feel terrible. Mistakes were made, etc. But the facts? He can't share them, because he can't bear them. He comes close, walks right up to the edge of the abyss, peers over. But then he always backs away slowly.

He's a natural storyteller. He can talk all day about a bad game, about a shattering disappointment, about his father leaving, about sleeping on the filthy blue couch at the Boys Club, waiting for his mother to get off work and come pick him up after baseball. But to tell a story in which he's the villain? It's like purposely striking out, and that he physically cannot do. He'll try, he'll start to tell about that time he did that dumb thing, but the story veers off and ends up with him as the hero getting a Champagne bath. So when he starts to talk about his secrets, and winds up saying nothing about his secrets, he doesn't sound reticent or shady. He sounds stuck in a pattern. He sounds tortured.

One day, sitting with Dr. David, he makes a list. Five ways to become a better person. He roughs it out on a piece of scratch paper, then types it up back home in Miami, then prints it out, then cuts it into a perfect square, then laminates it, then slides it into his black billfold, and every morning before shaving he takes it out and spends a few minutes really thinking about what it says. It's a searingly personal list, but he doesn't have to worry about it falling into the wrong hands, because it's written in a kind of wind-talker code that no one could break, a blend of Dr. David patois and Rodriguezese. Basically, the five items are about respecting others, about being kinder and more compassionate to others, and demanding others do the same. But there's nothing in there about making an explicit public avowal. Either it's not a priority for him or it's not in the realm of possibility.

He's shown his laminated wallet list to only three people.

One of them is Natasha.

“Saying nothing about his secrets, he doesn't sound reticent or shady. He sounds tortured.”

-

SHE'S NEVER DONE this before. She's always vaguely understood that her father is famous, that he has access to other famous people, but she's never asked him to use his fame and access to benefit her -- until now. She's mature enough to know that she's breaking precedent, and she's hesitant about it, but she can't help herself: She just wants so badly to go to the Katy Perry concert in Brooklyn, July 24, 2014, and she wants -- no, needs -- to meet Katy after the show.

When she asks her father, he sighs. That's one tall order, sweetie. But he tells her he'll try.

He works the phones for days, trying to find some friend of a friend who might know Katy. No luck. He sends out feelers, asks people to work their contact lists, again comes up empty. He considers telling Natasha it's just not doable, Daddy's sorry, but he can't bring himself, so he stalls, and tries again, and eventually manages to score the phone number of Katy's manager.

He calls the guy and, voice quavering, makes the ask.

Pause. All right, the manager says. Be backstage after the show. We'll see what we

can do.

And so, as the final note of the final song is still reverbing through Barclays Center, Rodriguez and his daughters hurry backstage, and stand at the dressing room door, and take a deep breath, and knock. Out comes Katy, wearing a billowy white bathrobe, and Rodriguez introduces himself, and thanks her for doing this, and then turns to look at his two daughters and sees them-shaking. They're violently shivering, unable to make words. Oh god, he thinks, they're going to pass out. He's never seen them like this, he's never seen them awed by anyone, or anything, and yet it all looks familiar, somehow, because of course he's seen other children do this, thousands of boys and girls at ballparks across the nation,

whenever he and the Yankees arrive at the hotel or take the field.

Haltingly, he tells Katy that Natasha is 9, she'll be 10 in November, and Katy turns her electric blue gaze on Natasha and says hello there, and Natasha summons her voice and asks meekly if she could maybe please have a hug? Of course, Katy says, and she wraps her arms around Natasha, and Natasha holds on, won't let go, her little eyes shut tight, pulling in and radiating a kind of love that can't quite be quantified, or named. Ella then does the same.

Later, the girls are still unable to draw a steady breath, and watching them slowly come down off their Katy high, Rodriguez feels pleased, and proud, but also troubled. He thinks of times he maybe didn't give his full attention to those boys and girls. He thinks of times he could have given some child, some fan, what Katy has just given his girls, but didn't. He makes a solemn promise. He will be better.

Derek Jeter and Rodriguez share the field before a spring training game in 2007. Gene J. Puskar/AP Images

AS SUMMER ROUNDS into September, he slips into full training mode. His hip feels better, his mind feels better. He's been working out regularly, but now, with spring training five short months away, he turns it up several notches. Running, lifting, stretching, batting, Pilates, yoga.

Some days he's in Manhattan Beach, jogging up and down an enormous dune of white sand, a workout so punishing that athletes sometimes pass out and roll unconscious down the mountain and someone needs to call the paramedics. Some days he's in Miami, consulting with members of the Jamaican track team, undergoing two-hour soft-tissue treatments that make him shriek in pain. Often, late at night, he's studying film, breaking down his swing, inch by inch, trying to streamline it, trying to go back to first principles.

He only interrupts his training schedule for special things, like an event at his daughters' school. Or today's college luncheon.

Rodriguez has helped defray the tuitions of about 25 college students, often sons and daughters of single moms, and today he's meeting four of them. They're called Alex Rodriguez Scholars, which may be why they're a bit glassy-eyed at the sight of Alex Rodriguez, but his eyes are glassy too. Now that he has one college class under his belt, he's more college-obsessed than ever, and over fried zucchini and chicken tenders he quizzes the Rodriguez Scholars about their undergraduate experience, their career goals. One says she wants to become a sociologist. One says he wants to be a cancer doctor. Rodriguez looks amazed.

Toward the end of the luncheon, after he's bombarded them with questions, and listened intently to their answers, Rodriguez asks if they have any questions for him. Cancer Doctor raises his hand: Do you have a personal philosophy or life motto that you follow?

Rodriguez looks down. His face turns serious. It's Marketing 644 all over again. I like to go around the room and have my students ... It's also every press conference ever. Alex! Alex! Do you have any comment about ... ? But it's also different. He wants to help these kids, who are still looking at him with those glassy eyes, and so he tries to think of an answer, the perfect answer, which will simultaneously take into account that he's a good person who did bad things, but also that when he was a bad person he did some very good things, or maybe he doesn't even want to get into all that, doesn't dare to try to explain himself, because he's the last person who should try to explain Alex Rodriguez, he's not there yet in his education, and so he continues thinking, and thinking, and you can almost see the rotating multicolored pinwheel in his forehead, and when he finally starts talking it just doesn't come together, it's nerve-wracking for everyone, like a game of word Jenga, and when the word tower comes crashing down on the table with a clatter, Rodriguez smiles, and Cancer Doctor nods, the way he'll one day nod after he's just told someone they have three months left. Could someone please pass the fried zucchini?

IN EARLY NOVEMBER he agrees to give a talk at the home of Milken's daughter, Bari Milken-Bernstein. There will be a moderator, a question-and-answer session, 150 guests -- and alcohol. Why on earth would he agree to such a thing? Maybe it's his friendship with Milken, maybe it's his desire to get better at explaining himself in public. Whatever the reason, as the guests settle into their seats in the backyard, Rodriguez looks as if he wishes he were dead, or at least wearing his security hoodie.

The moderator begins. As I walked around tonight, he says, as I talked to some of the folks here, almost without exception each one of them said: Are you gonna ask him?

Nervous laughter.

The moderator looks mightily pleased with himself, though it's hard to imagine why. If he'd moderated the Paris peace talks, the Vietnam War would now be entering its 50th year. So yes, he says, haha, yes, I am, I'm gonna ask him!

Excruciatingly nervous laughter.

The moderator continues: Alex, you just got done serving the longest suspension in baseball history for PEDs. Tell us about that. What happened? Where are we now? What's going on? What was it like?

And while you're at it, is there a God, how did the universe start, and what's the deal with Kanye?

Rodriguez gazes at the moderator, then at the audience, then at some fixed point a thousand yards in the distance. Softly, he tells them it's been a nightmare. Very painful, he says, very humbling. And the worst part, he tells them, was that ... a lot of it was self-inflicted.

A lot of it?

He says a few more things, adds that he'd like to finish his career on a good note, answers a few softball questions, and that's it. Good night, folks. Get home safe.

All things considered, an abject failure. And yet the next morning, before his workout, Rodriguez is ebullient. He feels like St. Augustine after publishing his Confessions. It feels so good to have gotten all that off his chest. He's really turning the corner, he thinks, really learning how to talk openly about his troubles. His mood stays upbeat, unnervingly so, well into the afternoon, until his BlackBerry blows up. A tabloid has just posted bizarre comments from the wife of Rodriguez's cousin Yuri. She says Rodriguez is evil, calls him the devil, swears that he treated her husband for years as a slave. What's more, she says, once upon a time, as a show of disrespect or primal control or some sort of gangster disrespect, Rodriguez urinated on their house.

The Internet goes boom. The entire galaxy retweets the story, and Rodriguez understands. It's delicious. Not true, he avers, but delicious. If the story weren't about him, he'd be laughing too. Yuri and the Urinator. It's -- a hoot.

As the story builds and builds, as it goes from whimsical curiosity to lead item on the afternoon sports talk shows, Rodriguez retreats to his house in Hollywood. He recently bought it from an Oscar-winning actress, and tour buses still stop outside, and people still jump out and take pictures of what they think is Her front gate. Little do they know it's Garbo-Rodriguez on the other side, in deep seclusion, watching TV in his backyard and wincing at the latest scene in the surreal black comedy that always seems to be his life: stone-faced reporters debating whether or not A-Rod went peepee on his cousin.

A recurring memory: He sees himself as a rookie. He can't yet hit, hasn't yet deciphered big league pitching. He can't even figure out how to dress like a big leaguer. (Which is why, throughout his decadelong tenure with the Yankees, he tries to buy three custom-made suits for every rookie who walks into the clubhouse.) Finally, he's called into the office of his manager, Lou Piniella. We're sending you down, Piniella says. Rodriguez stares. He knows he's been struggling, but the minors? Really? He can't believe it. Angry, humiliated, he flees the ballpark, phones his mother from the car. He tells her he's coming home. He's done with baseball. He just wants to enroll at the University of Miami.

I'll lock the doors, his mother says. I won't let you in this house.

If he's so homesick, she says, she'll send him a piece of home. She'll send him Cousin Yuri.

Thus begins a long, toxic, doomed relationship, ultimately devastating to both men. Rodriguez has said publicly that Yuri was his right hand, then his supplier, that it was Yuri who introduced him to a performance-enhancing pill from the streets of the Dominican: boli. (The name must have rung

a distant bell.) Finally, it was Yuri, according to Rodriguez's testimony in his arbitration hearing, who introduced him to Tony Bosch, the pretend doctor in the fake lab coat, the man who owned the seedy anti-aging clinic Biogenesis -- and who would soon own Rodriguez.

Bosch offers elixirs far more potent than boli, magic beans that cure nagging injuries, restore energy, grow hair, shed pounds. And Rodriguez buys the beanstalk. A partnership is formed, with shattering results. By the time it's dissolved, Rodriguez's career is in shambles, Bosch is in jail. (He was sentenced to four years in prison on Tuesday.) And Yuri, sometime around Opening Day, will go on trial for distributing testosterone. Rodriguez will likely need a day off from the Yankees to testify.

Bosch or no Bosch, Yuri or no Yuri, what made him do it? He loves baseball too much,

he sometimes says elliptically. Baseball is a beautiful woman, he says, and the more you love her, the more you reach for her, the more she pulls away. But he also loves praise; he's always wanted to please people, and this desire to please seems to be at the heart of his worst decisions. He wanted to please fans, please teammates, please sports writers, and that meant hitting home runs, and in 2010 when his body was breaking down, when he couldn't hit anything, he was in hell. He could no longer do this wonderful thing he'd done since he was a boy, could no longer practice his art, because though baseball is sometimes a game, and sometimes a woman, what it really is to him is high art.

He's been studying art since he was a young man, collecting it since he first made real money. In New York he would routinely befriend young artists, leave them tickets at the box office so they could come see him play, and in exchange they had to let him drop by their studios. He'd sit in the corner of some dingy loft for hours, watching some intense kid paint or sculpt or draw, because it inspired him, sent him back to his own studio, the batting cage, with new dedication. His notebooks are full of ideas about the masters, daVinci, Van Gogh, Picasso, and if it's not quite true that he knows the Monet Room like the back of his batting glove, he's one of the few baseball players who's been there more than once. He identifies with the artist's hunger, the artist's need to make some noise, leave some mark. Also with the artist's sense that some divine voice speaks through him. If that voice can speak through a brush, why not a bat? Crushing a fastball high into the night above Fenway -- that's not art? You'd never say that if you'd done it.

But when that voice stops speaking? The silence is like nothing you've ever heard, or not heard, and the loneliness is not unlike death, because it is a foretaste of death. He'd do anything to get it back.

Anything.

Maybe it's not simply about cheating. Maybe it's more complicated. Maybe's it's also not

that complicated. If no one is more alive than the athlete in his prime, then no one understands the senescence that awaits us all better than the athlete suddenly not in his prime. Maybe every disgraced athlete is Dorian Gray, selling his soul to stay young, to retain his beauty and power. Hiding his true portrait from the world, he wakes one day in horror at the bargain he's struck.

Rodriguez thinks often about that first meeting with Bosch. Shaking his hand, taking what he gave with the other hand, which might have been sugar and lies -- his numbers went down for two years. He laughs: Only he, only a dope like he, would do that stuff and have the two worst statistical seasons of his career. And now ... Yuri's wife is calling him the devil. He gazes balefully at the TV, at his face on the screen, at the words below his face: A-FRAUD. He grimaces, stands, walks inside the house.

text

Henny Ray Abrams/AP Images

HE PLANS TO take the girls away for Christmas vacation, maybe out of the country, far from all the white noise and scary headlines, but then he hears from his friend Barry Bonds. He's been trying to get in touch with Bonds for weeks, to get together for a chat, maybe a workout, but their schedules are always in conflict. Now Bonds is back in San Francisco, so Rodriguez changes his plans, rents a house in Tiburon through New Year's and begins a series of sessions with baseball's all-time home run leader, the second-most notorious figure of the steroid era.

Regardless of the skepticism that haunts Bonds' legacy, regardless of how it might look when the two are pictured together, Rodriguez admires the hell out of Bonds, sees him as a mystic, a hitting scientist. He looks to Bonds for guidance only he can provide. Bonds has no peer as a hitter, Rodriguez believes, but especially as an older hitter, who stayed fresh and lethal into his 40s. Rodriguez wants to ask him a million questions.

They meet at a local college, and much of their days are taken up with Bonds tossing batting practice to Rodriguez, and mocking him.

You're not gonna break my record swinging like that!

Look at that swing -- whew, my record is safe!

Then they sit and talk about how to make that swing more compact, more fluid.

Then they run, break a nice sweat, Bonds encouraging, exhorting Rodriguez to step higher, faster, quick quick quick. Finally, with the late shadows creeping across the outfield, they stand at home plate, two old painters before a white canvas. Bonds tells Rodriguez to work at quieting his mind. Quiet mind, quiet body. It's the secret, Bonds tells him. Secret of hitting, secret of art. Secret of everything. Rodriguez knows this, though hearing it from Bonds is inspiring. Later, when he talks about Bonds, when he demonstrates what Bonds said about quieting mind and body, he makes a startling gesture, puts his palms together in the middle of his chest, almost like the prayer pose of Buddhist meditation.

The other thing to remember, Bonds tells him: sleep. You can't get enough, especially if you're an older player. Sleep, sleep, sleep.

So on New Year's Eve, his head swimming with Bonds' words, Rodriguez craves a good night's sleep, but his daughters won't hear of it. They want to stay up. They want to drink soda until their ears bleed and watch Ryan Seacrest and have a dance party with some girlfriends, and also a costume party with Daddy and his friends. And not just costumes-onesies. Rodriguez sends someone to Target to buy onesies, and come dinnertime he's wearing a skintight pale purple Batman onesie, while his longtime pals Jose and Pepi are in Superman onesies, and they all can't stop giggling at the sight of one another.

Over dinner, Rodriguez-qua-Batman sits at the head of the table and watches his girls closely. Eyes shining, he asks them questions, prods them to say a few words about themselves. I like to go around the room and have my students ... He asks Natasha to tell everyone where she wants to go to college.

Princeton, she says, smiling. And then I'm going to get my Ph.D. at Oxford.

Oxford? He laughs. He beams. Oxford!

Daddy, Natasha says, where did you go?

He stops beaming. He looks stunned, breathless. He tells her that Daddy went to the University of Miami, for a short time, a little bit. He holds his thumb and forefinger a quarter-inch apart. But Daddy is going back. Daddy's going to get his degree.

Oh, she says.

Ella asks if they can play Monopoly later, if they can finish the game they started earlier. They talk about who was winning, and who owned Boardwalk and Park Place, and all those side deals Ella was making, the negotiations that prolonged the game. Rodriguez tells her that they can finish the game, but they have to play by the rules.

OK, she says.

The girls are so excited about being allowed to stay up past their bedtime -- they need to burn off some of the excitement. They ask if they can start the dance party. They don't wait for an answer. They crank the stereo, all their favorites, and go twirling and hopping and lip-syncing around the living room.

Catch me at the X with OG at a Yankee game.

Shit, I made the Yankee hat more famous than a Yankee can.

Rodriguez laughs, and sings, but mostly sits and watches, tickled.

Close to midnight they all run to the living room and gather in front of the TV. Ten, nine, eight ... Ella looks as if she's going to pop. As the ball drops in Times Square, everyone kisses and hugs and wishes one another Happy New Year, then gulps 12 grapes, a Spanish tradition that guarantees luck in the coming 12 months. Reluctantly, the girls go off to bed, and Rodriguez and his friends move outside to the patio.

Smoking big Davidoffs, Jose and Pepi talk about what lies ahead. Pepi calls Rodriguez Gumba; his children and Rodriguez's daughters call one another Gumbita. They talk about the future, because that's what men with cigars always do eventually. Then they dare to talk about the past. The past is usually dark and foreboding, like the old Tiger Stadium, and no one likes to go there, but Pepi tonight is keying on 2009, when Rodriguez told all the haters, Silencio. With the lights of San Francisco guttering like candles in the cold fog, Pepi, whose father gave Rodriguez his first pair of cleats, recounts every highlight from that fall, when Rodriguez crushed six home runs and drove in 18 and almost single-handedly vanquished Minnesota, Anaheim and Philadelphia to win the World Series.

Rodriguez listens, smiling wanly. Long night. Long year. His Batman suit is wrinkled, his utility belt is all cockeyed. He seems thoroughly worn out. But as Superman keeps talking, and talking -- You remember, Gumba? -- a gleam returns to his eye.

Batman looks as if he wouldn't mind grabbing a bat right now.

“His bat isn't quiet. Each time he connects, it sounds like a Civil War cannon. One, two, three balls go flying over the wall.”

-

A DOZEN MEMBERS of the Christopher Columbus High baseball team stand along the top step of the dugout, staring in awe. Another half dozen stand in the outfield, also staring in awe, when they're not shagging grounders and fly balls. The awe is natural: Fricking A-Rod is taking batting practice on their field. But it's magnified tenfold by the fact that he's wearing their uni -- a dark blue Columbus High T-shirt.

It goes well with his Yankee hat.

He's wearing the shirt for them, to remind them that he played here, that he was one of them, though he sounds as if he's still one of them. Talking about his freshman year at Columbus, he sounds an awful lot like a shy, skinny, awkward 14-year-old desperate to make the team.

Shockingly, he didn't make it. Coach told him he wasn't good enough. So with the help of a growth spurt and a scholarship, he transferred to a private school nearby and became a star. Thus, coming back here tonight is about more than getting back to his roots. It's about getting back at his roots, letting his roots know who's boss.

One of the boys hacks the ballpark sound system, puts on some music. As the old wooden ballpark shakes to the bass, Rodriguez gets loose, takes a dozen swings with just one arm, to tighten and strengthen tiny core and side muscles that most people don't think about, let alone use. Then he starts to unload. Balls begin slamming out of the yard. The work with Bonds is paying off. Rodriguez instantly looks locked in, looks as if he's quieted his mind to a Walden Pond stillness.

His bat isn't quiet. Each time he connects, it sounds like a Civil War cannon. One, two, three balls go flying over the wall, where it says EXPLORERS. The boys whip their heads around, watch the balls soar into the outer darkness. Four, five, six balls sail toward the lights, prompting oohs and ahhs from all directions. Cars are now pulling off the road and people are watching. Seven, eight, nine balls go whirling over the center-field fence, and the left-field fence, and two boys beyond the fences scurry

in the underbrush to retrieve them. Some balls are screaming line drives, others are graceful arcing rainbows, and some just hang in midair, like big asterisks.

The unseen DJ now puts on Jay Z.

Make a Yankee hat more famous than a Yankee can ...

Rodriguez is settling into a sick rhythm, his Columbus T-shirt sopping -- 11, 12, 13; when he finally, reluctantly, steps out of the cage, he's clouted 27 home runs. He towels off, grins. Before going to dinner at a chicken joint up the block, hard by the house where he grew up, around the corner from the restaurant where his mother waited tables, he poses for photos, signs autographs, goes up and down a sort of receiving line, a delegation from Puberty Town, shaking each boy's hand, asking his name, thanking him.

Later Rodriguez is smiling, laughing, and yet he concedes the night is tinged with melancholy. When his swing feels this good, when everything feels this good, he thinks of the what-ifs. What if he hadn't been so stupid. What if he hadn't -- you know. Pocket aces. But maybe this upcoming season, which is now just weeks away, maybe he can begin to set things right. If not make people forget, maybe give them some new memories. Maybe with enough home runs ...

Days later the Yankees say they're going to contest Rodriguez's contract, try to negate the $6 million bonus if he hits six more home runs and ties Willie Mays for fourth place on the all-time list.

WALKING OUT TO the plane, he puts his arm around his mother, holds her tight, and she leans into him, holds him tighter. They stay this way all the way across the tarmac. It's Jan. 14, 2015, an exciting day for them both. She's catching a ride to New York to visit old friends, he's scheduled to visit the offices of Major League Baseball, and then his doctor. Both meetings will go a long way to determining his future.

He guides her to her seat, visits with her a bit, then moves to the front of the plane and sits with a book on his lap. Den of Thieves, by James B. Stewart, an account of the insider-trading scandals of the 1980s. The book has plenty of fascinating tidbits about his friend, Milken, but Rodriguez isn't in a reading mood. He's keyed up, focused on what lies ahead.

He lands late, goes for a quick lunch in Midtown -- grilled fish, no oil, no salt, no butter, a cup of hot green tea -- then walks briskly down Madison Avenue. People passing him on the sidewalk smile, wave, cheer. One burly older man, changing liner bags in a garbage can, barely looks up, just cuts him a quick glance. Good luck this year, my brother. Rodriguez, taken aback, thanks him.

He's slated to meet Pat Courtney, baseball's communications officer, but moments after they sit down, in walks Rob Manfred, the commissioner-elect. Rodriguez jumps to his feet, shakes Manfred's hand. He jokes that he wishes they were meeting on a different floor -- this floor hasn't been good for him, historically. The energy is way off. He's having flashbacks, he tells them, laughing, and they

all chuckle, because they are too, back to the grim scene a year ago.

It was in an adjacent room. Sitting at a vast conference table, surrounded by lawyers, some of them his, some of them baseball's, Rodriguez lost it. Upon learning that Selig wasn't going to show, wasn't going to testify at his arbitration hearing, Rodriguez stomped around the table, did something like the opposite of a home run trot, and shoved a chair, and shouted: This is fucking bullshit! Then he stormed out, left the building in a cloud of righteous indignation, as if he were the innocent victim of some terrible miscarriage of justice. (Hours later he swore his innocence to Mike Francesa on live radio.)

Now, after months of fence-mending, and lying low, and doing everything Manfred asked of him, plus therapy and introspection and rest and a few dozen private telephone apologies, Rodriguez tells Manfred he's in a much better place. Manfred agrees. In fact, he says, as far as baseball is concerned, the suspension is a closed matter. He welcomes Rodriguez back to the fold.

Rodriguez thanks Manfred, and Courtney, shakes their hands, then floats down in the elevator. He sails out of the building into an icy-cold wind -- snow on the way. But he looks flushed, warm. He looks giddy. He looks reborn.

He hurries uptown to the Hospital for Special Surgery. A nurse whisks him into a sort of closet, hands him some shorts made of blue paper. He puts them on, comes out, looks uncertainly at the nurse, at everyone, as if trying on a suit at Barneys. She leads him into a dark room, stretches him out on a table, under a multiheaded camera, and just like that his good mood is gone. He looks like a frightened little boy as the nurse leaves the room and shuts the door and punches a few buttons on her console, next to a label: Alexander E. Rodriguez DOB July 27, 1975. The machine hums, whirs, takes several X-rays of Rodriguez's pelvis. He stares at the ceiling, purses his lips. What if it's bad news? What if the hip is impinged again? What if, after all this -- ?

The nurse opens the door, tells him to come, leads him to a tiny exam room down the hall. Within seconds, in walks Dr. Bryan Kelly, a boyish, squarely built man in a crisp white lab coat. They hug, laugh. You look good, they both say, and they immediately begin reminiscing about the day they met, exactly two years ago, in this very room. Rodriguez was having none of Kelly. He wasn't feeling like himself and he was out of patience with doctors. Hunched over, wearing a hoodie, he was staring at the floor. Kelly talked to him softly, kindly, won his trust. Then dropped the hammer. You've got three stark options, he said. Play with a compromised hip. Try a miracle surgery with little chance of success. Or retire.

Rodriguez didn't hesitate: Miracle surgery.

Others thought it was a terrible gamble. Among them was the physical therapist who helped Rodriguez recover from his first hip surgery in 2009. Kelly recalls the therapist seeking him out the night before the 2013 surgery, walking into his office and getting down on his knees. Please do not do this, he begged. Alex Rodriguez will never be the same if you do this.

On his knees.

But it wasn't Kelly's call. It was up to Rodriguez. And Rodriguez was willing to do anything, risk anything, to get back.

Anything.

Now Kelly puts the X-rays of Rodriguez's hip on the lightbox. He shows Rodriguez where the impingement used to be. Still gone, he says: Everything looks good. Rodriguez exhales.

Kelly sits heavily in a chair. Go out there and tear it up, he says. I know you can do it. I don't have a doubt.

Rodriguez looks as if he might weep. He tells Kelly that he's going to get him some tickets. He's going to get him a box. One night this season, he says, Kelly has to come see him play. He has to. He just has to.

Rodriguez repeatedly says he's not coming back for the money -- but who believes him? Peter Hapak

HE'D HOPED TO fly to the mountaintop for one more session, but Dr. David is all booked up this month. So they'll probably Skype. He just wants to go over it one more time, how to handle the various pressures when he returns, how to stay on this path. And of course they'll talk a bit about the most important obstacle in his path -- his meeting with Natasha.

Often he'll look at his older daughter and it will all come back, so terribly clear, how the world appears to a 10-year-old's eyes. (In fact, some days he wishes he could forget.) She is him. He is her. And yet she's so much more grown up than he was at her age.

Sometimes, when she's doing her homework, or commanding him to find them a good song on the radio as they drive to school, he recalls the night she was born. Cynthia waking him: Alex, it's time. He sees them racing to the delivery room, Cynthia being a trouper, him being a wimp. Not only did he become dizzy, not only did he throw up -- he almost passed out. They had to lay him on the hospital bed alongside Cynthia. A nurse put a cold compress on his forehead, and took his blood pressure, and everyone laughed at him, the big strong Daddy. Even he had to laugh. Pitiful performance. But he was just so excited, so nervous.

Then the room filled with people. Doctors, nurses, relatives, close friends, everyone talking at once to him and Cynthia, and then all the people left, and then there was screaming, much of it his, and suddenly there was a new person in the room, Natasha Rodriguez, 1 minute old, wanting what everyone wants. To be warm. To be held. To be safe. To be known.

He and Cynthia knew her name before she got here. For years they'd agreed that the name Natasha was beautiful, exotic, kind of Russian, but also kind of Spanish, and when they saw her they had no doubt.

Cynthia will be in the room when he sits down with Natasha, and though Natasha will be listening to him, most of the time she'll be trying to mind-map her mother, he thinks. Good thing too, since he's sure to fall apart. He knows he's going to cry, and once he starts, it will be hard to stop. But he'll just have to gut it out, choke back the tears, tell her the truth. He plans to tell her the whole truth -- edited for a 10-year-old, but still, the most complete accounting he's ever given anyone.

He doesn't know exactly what he's going to say, what words he'll use, and he can't imagine what she'll say. But she's the daughter of Alex Rodriguez -- she has his eyes, his smile, her middle name is Alexander -- so she's likely to have a lot of questions.

He wishes he didn't have to answer them. He'd give anything not to have to do this. She's the same age he was when his father disappointed him, and now he's got to disappoint her.

And yet there's also a part of him that's proud. This is what fathers do. Fathers explain the world. I didn't have a father telling me a fucking thing, he says, suddenly angry. I was cheated, he says.

So the cheating stops now.

He hopes, in the end, his answers satisfy Natasha. If so, she'll be the first. If not? At least, when it's all over, he hopes they both will have learned something.

He lives in hope.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "The Education of Alex Rodriquez."