The other day I watched video streaming live from someone’s phone on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The picture was small and jerky, but mesmerizing. I was thousands of miles away, watching dusk fall over the Grand Canyon through someone else’s eyes. Soon dozens, then hundreds of others from around the world were watching with me.

I could see their Twitter names pop up as they joined through the new Periscope app. People from Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Turkey and Chile chimed in with virtual “oohs” and “aahs” befitting the occasion.

The experience proved that at their best national parks are a shared experience, made more meaningful the more who treasure them. They are an American invention, owned by all of us, preserving our history, nature and culture for all of us to treasure and to share.

And now they need your help. You can help save them, by sharing them.

Traditional park visitors are aging and proliferating electronics are challenging the parks for relevancy. Park visitors are disproportionately white and well-off. The old image of a grand loop vacation through the great parks seems an anachronism in today’s diverse and hyper-connected world, when you can fly across an ocean more quickly than it would take many of us to drive to a major park.

I helped highlight these trends. My articles are cited in the book, “Last Child in the Woods,” the bestselling story of why kids are losing touch with the land and why it matters.

The National Park Service knows this, and has launched a centennial initiative to change it. The centerpiece is a “Find Your Park” campaign encouraging people to reconnect to essential park experiences and realize the diversity of a modern park system that extends to Rosie the Riveter and Freedom Riders. It’s interesting, ambitious and it needs you.

The first time the parks went viral

A little more than a century ago, Stephen T. Mather faced a similar challenge. The first national parks had just been created, but few knew much about them. Some were getting trashed and pillaged. If the parks were going to survive and thrive, Mather knew, he had to make the country fall in love with them and view them as part of ourselves. The millions who love the parks today are a testament to his success.

And Mather’s playbook is still relevant, even if the tools have changed.

Mather was above all a public relations genius. He did not go anywhere without engaging the press and using all the allure of the fledgling park system to build affection for the parks and a new agency to run them. He hired his journalist friend Robert Sterling Yard out of his own pocket and they pumped out articles, producing a lavishly illustrated volume called “The National Parks Portfolio” that cemented the parks as special places in a category by themselves.

It was a hit, republished several times (the equivalent at the time of going viral) and a version for kids became a bestseller.

But Mather also recognized the importance of human touch, of building relationships and appreciation in key allies and influencers who could spread the word.

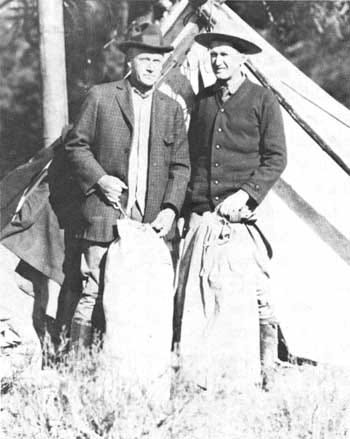

So in 1915 he planned a trip, an all-out pitch for the parks and Park Service with those who could share it with the world. He invited a finely tuned mix of authors, museum presidents, publishers, influential politicians and businessmen he wanted aboard his bandwagon.

It soon became known as the “Mather Mountain Party.”

“It was a grandiose scheme,” Mather’s number-two man and alter ego Horace Albright wrote later. “But by now I knew him well enough to realize that the expedition would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience and just his style.”

Your turn to spread the park gospel

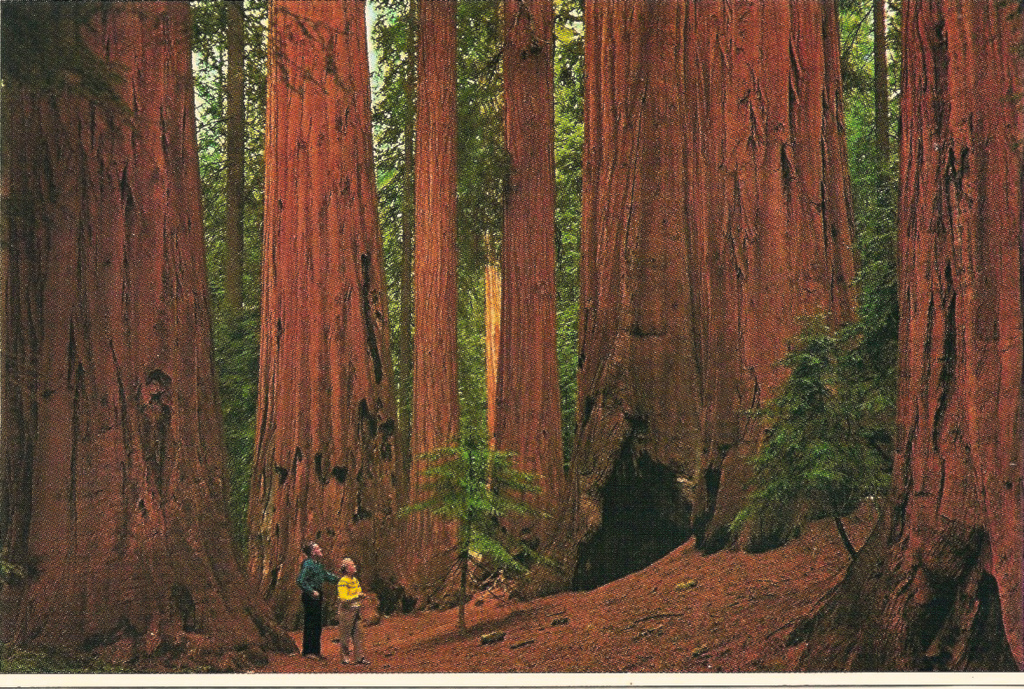

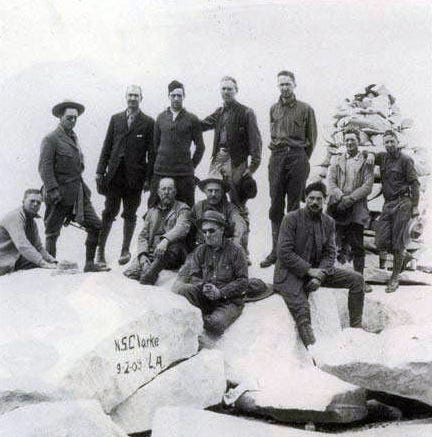

Mather directed them to leave their suitcases and city clothes behind and led them up rocky trails into the high country of Sequoia National Park and what would later become Kings Canyon. They slept under the sequoias, climbed Mount Whitney, cleaned up trashed campsites, lost a mule with half their food, soaked in hot springs, marveled at mountaintops and got caught in snowstorms.

And they loved it. It was on that trip that national parks may have gained their most important evangelists, those who could translate what they saw into an enduring American institution. As Mather told them at the trip’s end, “To each of you, to all of you, remember that God has given us these beautiful lands. Try to save them for, and share them with, future generations.

“Go out and spread the gospel!”

They did. Now it’s time for you and me to do the same.

It’s time for a modern Mather Mountain Party, made up of all of us who have seen and savored and loved the national parks, to spread that gospel to others, to build the connection between a new generation of Americans and a new generation of national parks. The challenge is just as crucial as the one Mather faced: establish, or in this case, reestablish the national parks as part of the fundamental American experience.

I am fortunate to have lived next to Yellowstone National Park for more than a decade: I’ve hiked its backcountry crannies, watched its wolves and bears, waited in the moonlight for a favorite geyser to explode. Now a city dweller, I share that gospel with my neighbors, coworkers, people I meet at bars, you name it. You can find your park, near or far, and do that, too.

The same electronic connections that today distance us from the world around us make sharing that world as easy as ever, just as that video stream from the Grand Canyon showed me the other day. It’s time to share the parks, and the awe they inspire. If Mather could do it, so can we.

Michael Milstein is a onetime park ranger and longtime environmental writer. This piece originally appeared on Medium.